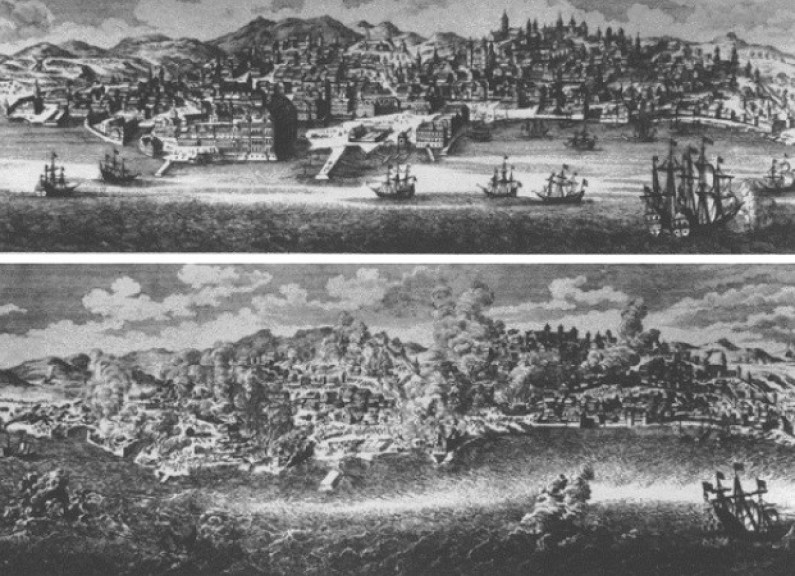

A new era began in Lisbon on 1 November 1755, All Saints Day, when a devastating earthquake, one of the most powerful in recorded history, destroyed two thirds of the city. The first shock struck at 9:40 a.m., followed by another tremor at 10:00 a.m., and a third at noon. Many persons rushed to those squares beside the River Tagus with enough space to escape the collapsing structures of the city, but were drowned by a 7-metre high tsunami that flooded the river’s mouth about half an hour later. After the earthquake, the tsunami, and subsequent fires, Lisbon lay in ruins. The large Royal Turret, the Casa das Índias, the Carmo Convent (Convento da Ordem do Carmo), the Court of the Inquisition, and the Hospital de Todos-os-Santos were destroyed. Thousands of buildings collapsed, including many churches, monasteries, nunneries, and palaces. Of the 20,000 less solidly built houses of the lower classes, 17,000 were destroyed. Many buildings occupied by the rich in the Bairro Alto neighbourhood survived, as well as some buildings made of solid stone in a few other areas. Major fires raged in the city for six days and there was rampant looting. Of the city’s 180,000 inhabitants, between 30,000 and 60,000 died, while many others lost their entire property. The Marquis of Pombal, who was inspired by the new political, economic, and scientific theories of the Enlightenment and had such influence over the king that he was de facto ruler of Portugal, seized the opportunity presented by the catastrophe to implement in Portugal some of the liberal reforms that had been tried successfully in other western European countries.

In 1756, the French philosopher and voice of the enlightenment, Voltaire, published a poem entitled Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne (“Poem on the Lisbon Disaster”) which expressed the shock and disillusionment of European intellectuals after the Lisbon earthquake, as well as his own rejection of the philosophical optimism popularised by the English poet, Alexander Pope, in his poem, An Essay on Man. Voltaire subsequently used the catastrophic event in his novella Candide, published in 1759, to satirise Leibnizian optimism, religion, and war.

Military engineers and surveyors under the supervision of chief engineer General Manuel da Maia (1672-1768), Colonel Carlos Mardel (1695-1763), and Captain Eugénio dos Santos (1711-1760) were ordered by the Marquis of Pombal to draw up plans for the rebuilding of the city, to inventory property claims, and to ensure that debris was removed safely and the bodies of the dead were disposed of in a sanitary manner. The Águas Livres Aqueduct (Aquaducto das Águas Livres), built by order of John V and put into service in 1748, was so well constructed that it was unharmed by the earthquake of 1755; it had 127 masonry arches, the highest of which is in the stretch crossing the Alcântara valley, and is 65 metres (213 ft) high.

As part of the reconstruction of downtown Lisbon, a new naval arsenal was erected by order of Pombal at the same site on the banks of the Tagus, west of the royal palace, where many of the ships of the Portuguese age of exploration were built, among them the naus and galleons that had opened the trade route to India. It was a vast building containing naval magazines and offices of different departments of the naval service. Renamed the Arsenal Real da Marinha (Royal Navy Shipyard), the official maritime works of the Ribeira das Naus continued operating there as in the expansive days of Manuel I, who had ordered the construction of new shipyards (tercenas) on the site of the medieval shipyards.

Marquis of Pombal

The 1st Marquis of Pombal, who had been born into the lower-ranking nobility, became effectively prime minister to Joseph I, after brief careers in the Portuguese army and the diplomatic service. He famously responded to the king’s query regarding what he should do about the devastation caused the earthquake: “Bury the dead. Feed the living. Rebuild the city.” This was a succinct expression of Pombal’s approach to the recovery of the city’s economy and social structure.

The marquis, after he had ordered a review of the actual situation through an unprecedented population survey, refused the counsel of some of his advisers who wished to move the capital to another city, and initiated reconstruction in Lisbon according to new theories of urban planning.The royal income from Brazil paid for almost the entire reconstruction project, its cost amounting to over 20 million silver cruzados. The city also received emergency aid from England, Spain and the Hansa, and subsequently filled with construction sites. Most of the Portuguese aristocracy took refuge on their country estates around Lisbon, while King Joseph and his court took up residence in a huge complex of tents and barracks built in Ajuda, on the outskirts of the city. This became the centre of Portuguese political and social life for a couple of years after the great earthquake, while repairs were made on the royal palace in Belém, then still an area outside the city.

Church of Saint Anthony, in Lisbon, the birthplace of Saint Anthony of Padua, also known as Anthony of Lisbon. It was fully rebuilt after the 1755 earthquake to a Baroque-Rococo design by architect Mateus Vicente de Oliveira

.

Most of the reconstruction was carried out, however, in the old city centre with a new layout, approved by the marquis and designed by Eugenio dos Santos and Carlos Mardel, for the Baixa, the neighbourhood hardest hit by the earthquake. Their plan fit the pragmatic spirit of the age of Enlightenment, with the narrow old streets being replaced by wide straight avenues arranged orthogonally. These not only allowed proper ventilation and lighting of the streets, but also allowed for better security, including police patrols and access to buildings in case of fire, as well as measures to prevent the spread of fire to neighbouring structures. The buildings had to conform to regulations based on a consistent policy, with the architectural team defining which façade designs were allowed, and the rules of construction for all buildings. They aimed to reorganise the social structure of the city, with a new emphasis on mercantile business, and developed a set of rules for the construction of housing better able to survive a powerful earthquake.

The critical architectural innovation designed for this purpose consisted of a wooden skeleton called the gaiola pombalina (Pombal Cage), a flexible rectangular frame with diagonal braces enabling structures to withstand the overload and stress of an earthquake without coming apart. This wooden frame was erected atop walls with barrel vault arches on a masonry foundation, giving solidity and weight to the first floor of the buildings, intended for occupation by shops, offices and warehouses. All new structures in the downtown area were erected on pine log pilings driven into the sandy soil of the Baixa, to ensure the effective support of their weight. They were arranged according to their importance in a horizontal hierarchy based on proximity to the street (the uppermost storey would be reserved for poorer families with few possessions, usually having lower ceilings, communal balconies, smaller windows and smaller rooms). All the buildings had masonry firewalls separating them from each other. The standardization of facades, windows, doors, simple geometric patterns in the hallway tiles, etc. permitted accelerated progress of the works through the mass production of these elements on site.

The entire area was laid out along neo-Classical lines with classical proportions according to architectural rules of composition using the golden ratio. The structural core of the new city was the Rua Augusta, connecting the northern limit of the city, the Rossio, and the southern boundary, the Praça do Comércio, commonly referred to as the “Terreiro do Paço” (Palace Square), opening onto Rua Augusta through the triumphal Arco da Vitória (erected to commemorate the city’s reconstruction but not finished until 1873). This plan is integral to the design of what was intended to be the new heart of commercial activity in the reconstructed city. The buildings surrounding the Palace Square were built to contain warehouses and the large commercial buildings expected to stimulate mercantile activity in the plaza, but after several years of abandonment were eventually occupied by government ministries, courts, the Navy Yard, the Customs building, and the stock exchange during the reign of Queen Maria I.

A new market was designed, although it was ultimately never built, at the north end, parallel to Rossio, at the square originally called Praça Nova (New Square), and today known as the Praça da Figueira. Despite their fervent desire to complete the project, rebuilding Lisbon took much longer than Pombal and his staff expected, its reconstruction not being completed until 1806. This was due largely to the lack of capital among the bourgeoisie of a city in crisis. With ruthless efficiency Pombal limited the power of the Church, expelled the Jesuits from Portuguese territories and brutally suppressed the power of the conservative territorial aristocracy. This led to a series of conspiracies and counter-conspiracies, culminating with the torture and public execution in 1759 of members of the Távora family and its closest relatives, who were implicated in a plot to assassinate the king, dispatch Pombal and put the conservative Duke of Aveiro on the throne. Some historians argue that this charge is unsupportable, that it was a hoax perpetrated by Pombal himself to limit the growing powers of the old aristocratic families.

By the 1770s Pombal had effectively neutralised the Inquisition consequently the new Christians, still the majority of the educated and liberal middle class of the city and the country, were freed from their legal restrictions and finally allowed access to the high government positions previously the exclusive monopoly of the ‘pureblood’ aristocracy. Industry was supported in a somewhat dirigiste, but vigorous, manner, several royal factories being established in Lisbon and other cities that thrived. After the Pombaline period there were twenty new plants for every one that had previously existed. The various state-imposed taxes and duties, which had proven burdensome to trade, were abolished in 1755. Throughout the implementation of these initiatives by the Junta do Comércio, Pombal relied on donations and loans made by the merchants and industrialists of Lisbon. Signs of a recovering economy emerged slowly under the Portuguese economic renewal policy. The city grew gradually to 250,000 inhabitants who settled in all geographical directions, occupying the new neighbourhoods of Estrella and Rato, while its new industrial centre concentrated around the recent water supply brought by the aqueduct to the water tower of Alcântara. Many factories arose in the area, including the royal ceramic factory and the silk factory of Amoreiras, where mulberry trees were grown to provide leaves to feed the larvae of the silkworms used by the local silk factories. The Prime Minister tried continually to stimulate the rise of middle class, which he saw as essential to the country’s development and progress. The first cafes owned by Italians were founded in the city around this time: some survive today such as Martinho da Arcada (1782) in the Palace Square and the Nicola in Rossio Square, whose Liberal owner, among others, illuminated the facade after each Progressive political victory. The richest burghers acquired the habit of holding social soirées, with the unprecedented participation of women, while among the conservative nobility women held their traditional place and did not participate..In this manner a self-conscious bourgeois middle class rose again from the people of Lisbon, composed of both New Christians and Old Christians; these were the source of the national Liberal and Republican political movements, their presence manifested by the publication of several new newspapers in the capital.

Pombal was forced to resign after the death of King Joseph and the ascension to the throne of his daughter, the very religious Maria I, whose great contribution to the nation’s cultural patrimony was the building of the Basílica da Estrela. Under the advisement of the clergy and the conservative nobles, she dismissed the prime minister and sought to limit and even reversed some of his progressive reforms, a movement called the Viradeira. Economic conditions had greatly improved in the Pombaline era, but began to deteriorate under the new regime while budgetary problems mounted. To deal with rising poverty and crime, a police force was created in 1780 under the leadership of Diogo Pina Manique. Secular political persecution resumed at this time. The police hounded, arrested, tortured and expelled progressive partisans: Freemasons, Jacobins and liberals; as well as their newspapers, were censored. Many literary works by liberal Protestants or philosophers were banned and the cafes where they congregated were watched by plainclothes policemen. Cultural expression was controlled and any manifestations less than rigidly Catholic were outlawed, including the ancient Carnival. Conversely, Portuguese theatre was stimulated by the construction in 1793 of the Teatro de São Carlos in Chiado, which replaced the opera house destroyed during the earthquake. It was, however, funded by the private sector.

Comments are closed.